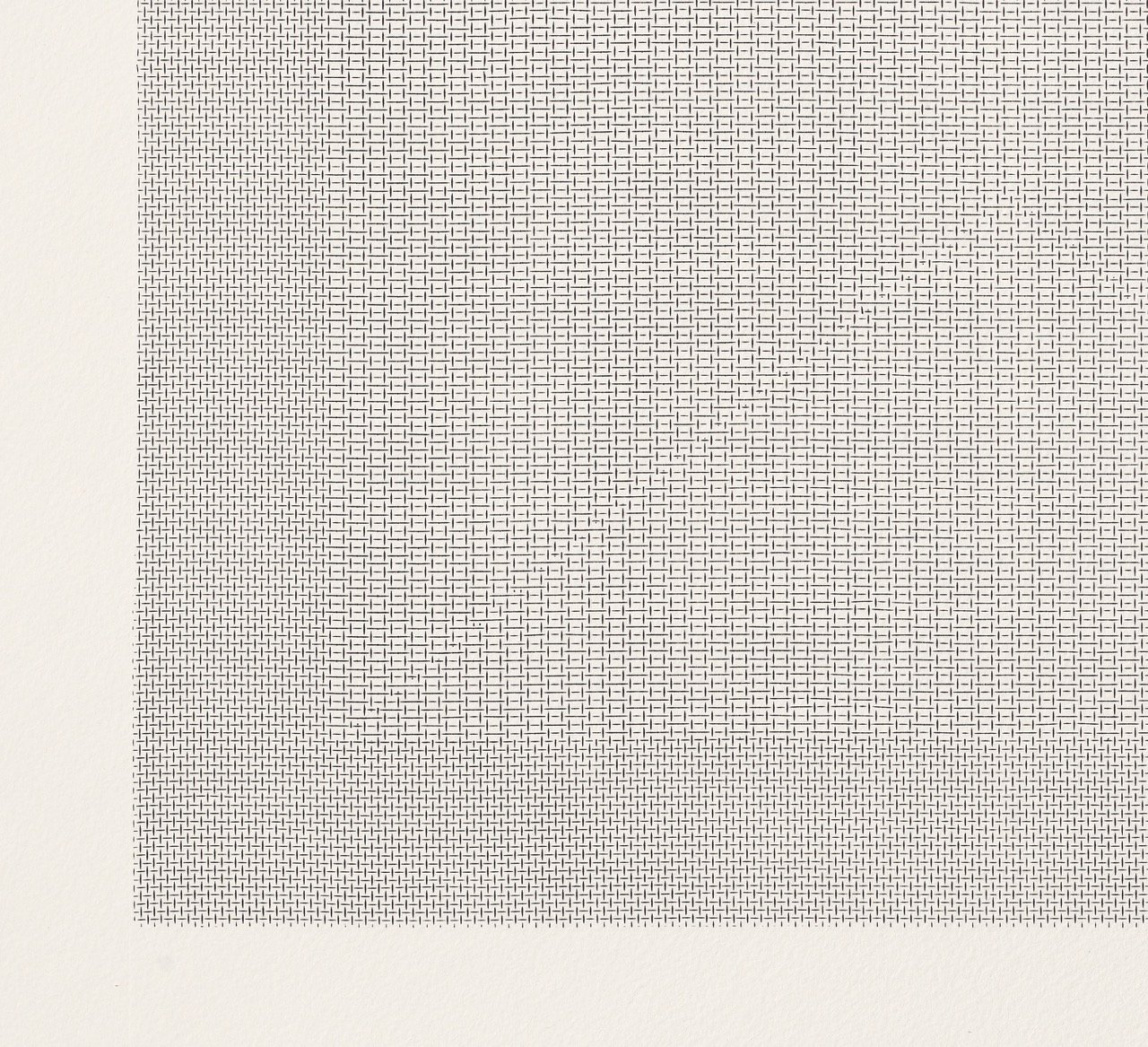

Tara Donovan

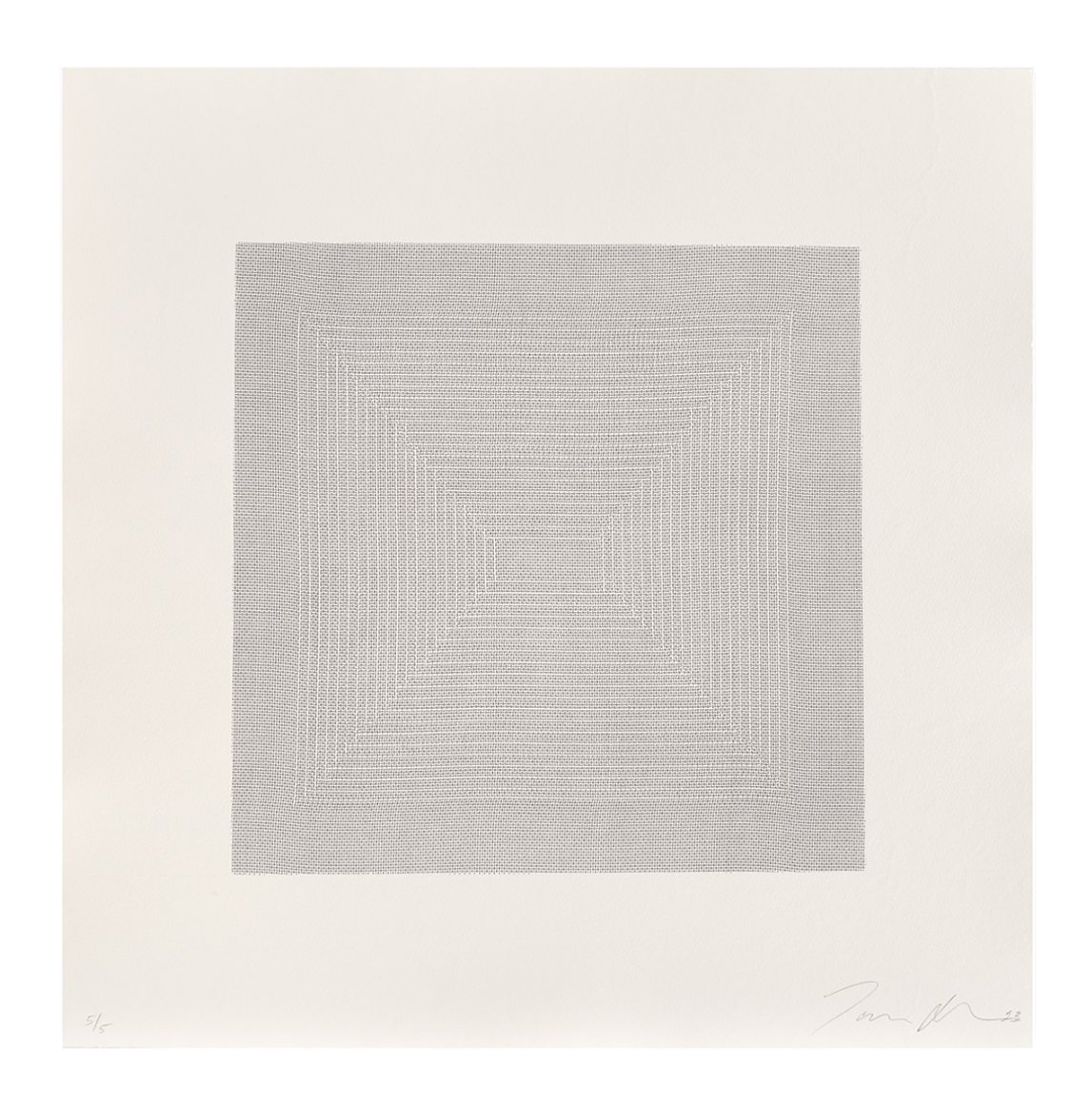

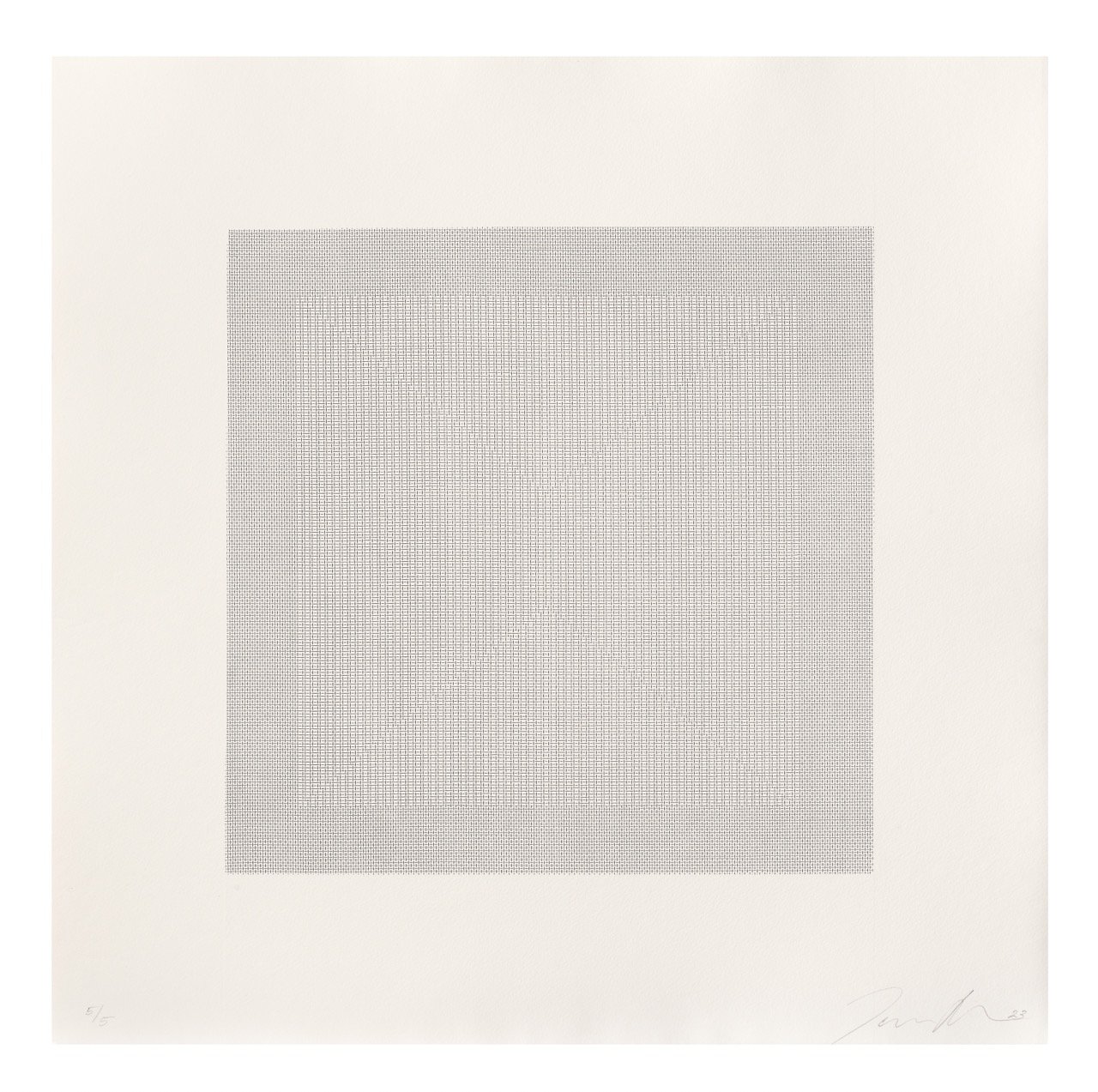

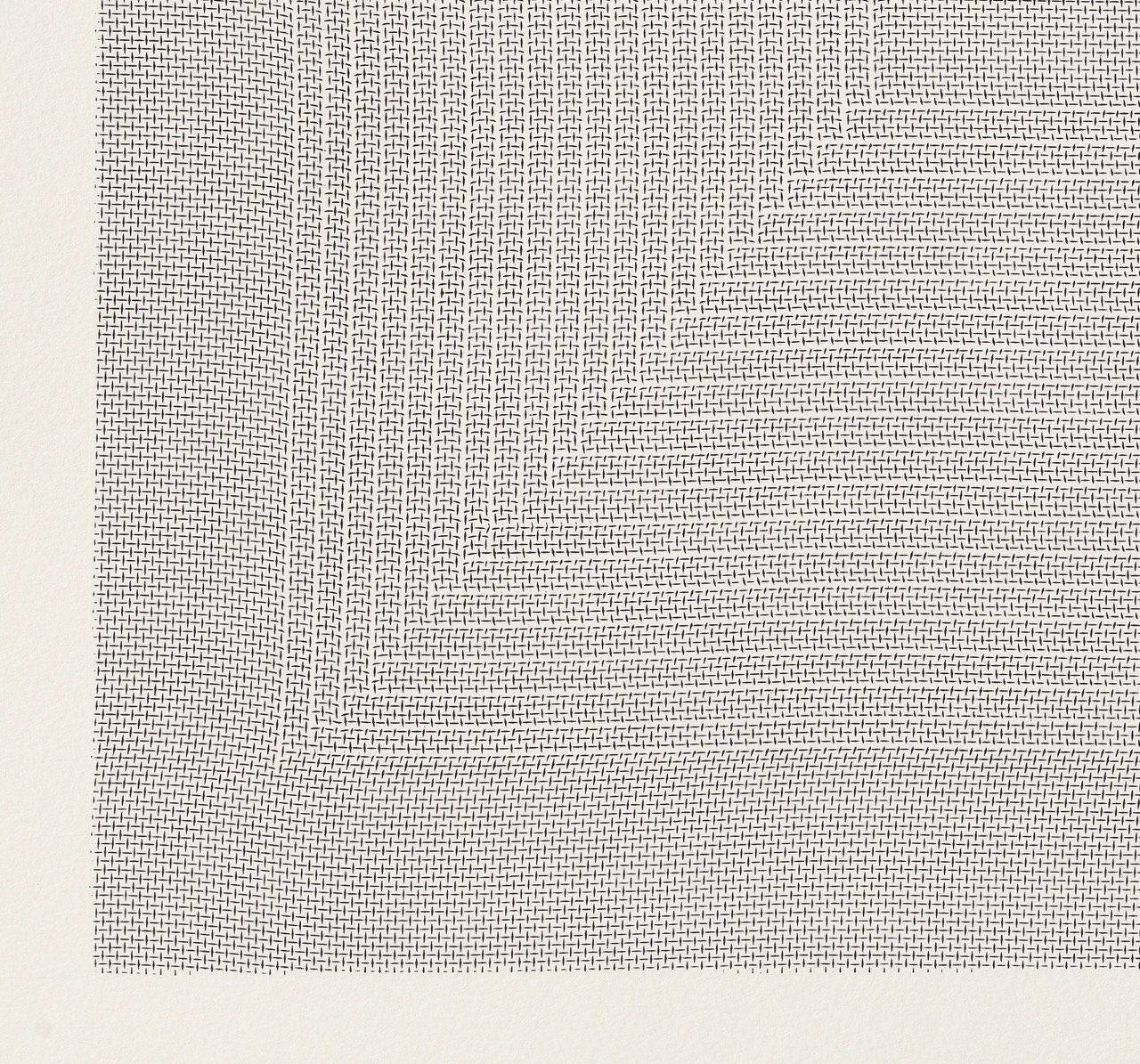

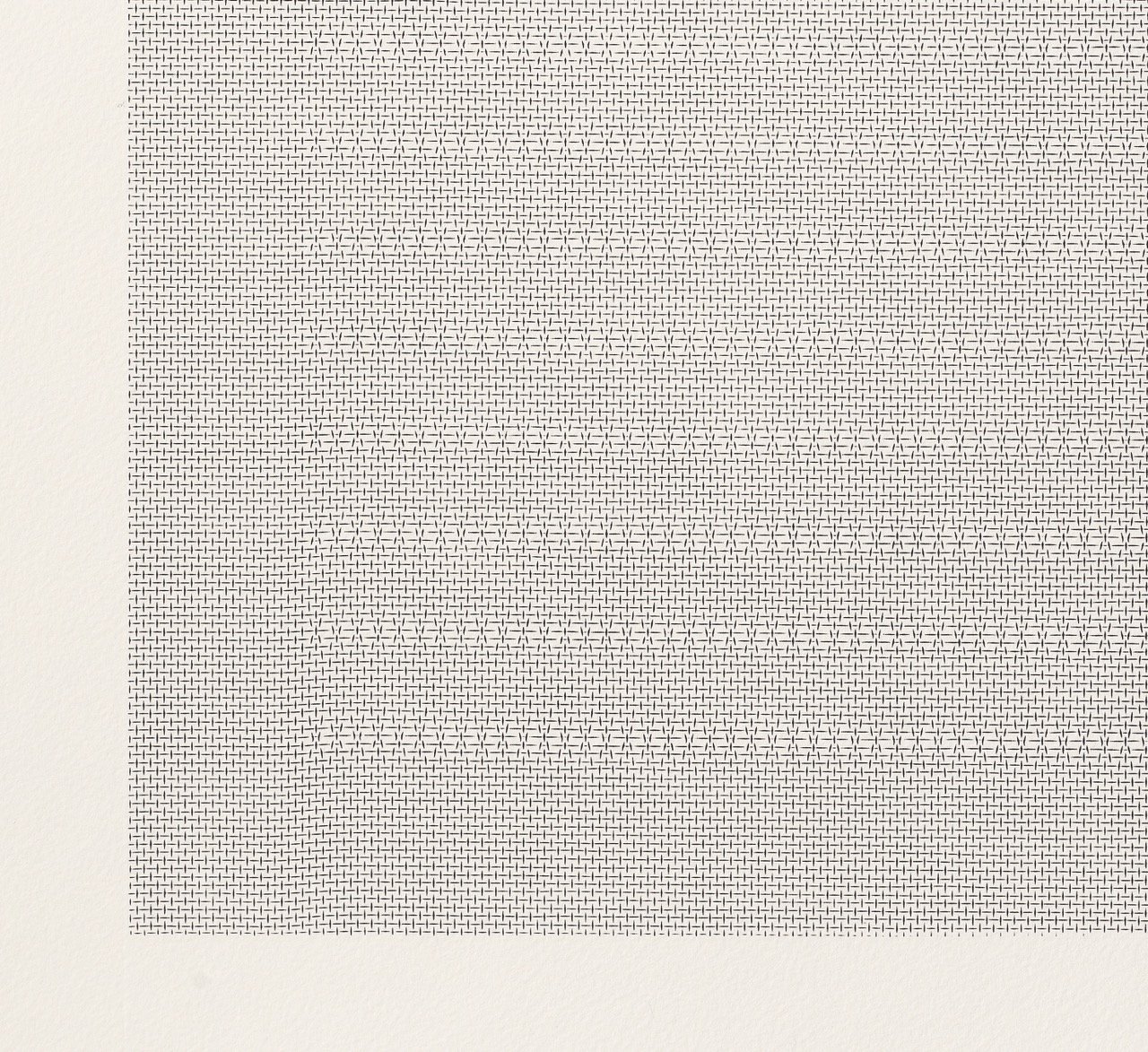

Untitled, 2023

Suite of four relief prints from aluminum screen matrices

23 ⅛ x 23 ⅛ in (58.7 x 58.7 cm)

Edition of 5

Co-published by Farrington Press and Josh Pazda Hiram Butler

Monoprints

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 17 3/4" × 23 3/4" in.

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 17 3/4" × 23 3/4" in.

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 17 3/4" × 23 3/4" in.

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 17 3/4" × 23 3/4" in.

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 23 3/4" × 17 3/4" in.

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 23 3/4" × 17 3/4" in.

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Untitled, 2024, monoprint, 36 1/8" × 28 1/8" in

Ruminations on the Most Recent Tara Donovan Works Published by Farrington Press

By Jennifer Roberts

Donovan starts with a razor blade, scraping the microthin foil from the surface of discarded CDs. She buys them in bulk for just fractions of a cent per disc. But in a way they are priceless, for these are not the kind of CDs that come pre-pressed with ready-made media content; these are the recordable versions, the CD-Rs. These are personal, even intimate: each filled with things that someone somewhere cared enough about to save. And you can imagine that it’s somehow all still in there, however flecked and tattered: shards of the last few chords of a favorite pirated grunge album, a few pixels shaved off the side of a family photograph, scraps of backed-up tax files, a run-on sentence from a ninth-grade English paper, the bottom half of the third line of an email from an ex-lover. All of it was once burned by a laser through a disc and into the reflective metallic layer on the underside of the label, leaving tiny deformations in the foil, a nanoscopic architecture of memory now strewn in ruins across Donovan’s prints.

If her streams of ripped and scattered foil seem violent, it is simply because they highlight what is already a catastrophe of obsolescence. Data abandoned in ephemeral media formats, tidelines of personal digital trash: so much has already been consigned to oblivion. Even so, there is something eternal about this glinting wreckage. The foils, for all their apparent transience, are made of gold and silver, elements far more ancient than the Earth, forged eons ago in supernova explosions and neutron star collisions. Cosmic mirrors printed with the passing reflections of a forgetful world.

Celestial references seem appropriate here, and it’s not only because Donovan’s prints look like scenes from outer space, or because the terms that seem best suited to describe the dynamics of her compositions—tidal torque, stellar streams—come from astrophysics. It’s also because they were made at Farrington Press, which is located at a working observatory. (Kyle Simon, master printer and citizen astronomer, built the print shop while also refurbishing the telescope and dome). The air at Farrington is classic observatory air: 6000 feet up, high desert, dry and lonely and rarefied, close to the stars. It’s air that makes connections to the heavens. And it also makes prints, in its own peculiar way.

Throughout the process of making the prints, Donovan’s wispy foil flecks kept getting swept up by static charges. The foil jumped and hovered and clung, as if all that dead dismembered data had been sparked back to life by electrostatic forces. The same dry observatory air that reveals the stars became an unruly collaborator, insisting on its own constellations. Donovan may have begun each gesture, flinging the foil out over the plate, but the static took it from there. Only a pass through the press could finally settle the composition down, sealing all that jittering glimmer into a bed of black ink.

But the foil is still not yet quiet. Because CD recordings are burned at the scale of visible light,hewn for optical wavelengths, even the smallest scrap of foil still serves as a diffraction grating, breaking the light into iridescent patterns, like beetle wings or abalone shells. We may no longer be able to decipher the fossilized data that Donovan has scraped back from oblivion, but the light can read it. And there, on the surface of the prints, it plays it all back, in shifting gleams of iridescent recall.

_

Tara Donovan creates large-scale installations and sculptures made from everyday objects. Known for her commitment to process, she has earned acclaim for her ability to discover the inherent physical characteristics of an object and transform it into art. Donovan’s many accolades include the prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Award (2008); and first annual Calder Prize (2005), among others. For over a decade, numerous museums have mounted solo exhibitions of Donovan’s work including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2007-2008), UCLA Hammer Museum (2004), and Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (1999-2000). Donovan’s work appears in numerous public collections including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.